Artists in their Studios

Notes by Edward Quinn, Nice 1995

For nearly half a century, since 1950, I photographed innumerable personalities, actors and actresses, politicians, businessmen, musicians, dancers, socialites, kings and ex–kings, in other words, everybody who made headlines at the time on the French Riviera, the Côte d’Azur.

I certainly appreciated to meet these people. But most of all, I enjoyed the company of artists. I believe they also liked my presence, as they usually accepted readily to be photographed. An affinity existed between us, a mutual respect and understanding for each other’s work.

When I started out as a photo reporter on the French Riviera, I was not acquainted with the names of many contemporary painters. Of course, I heard of Picasso and was aware that he lived on the Côte d’Azur. Picasso had a magical attraction to newspaper and magazine editors and very early on, I was informed a photo report on the painter would be very well received.

On July 21, 1951, I took my first photographs of Picasso. I read in the local newspaper that he would be the guest of honor at the opening of a ceramic exhibition in Vallauris and decided to attend. Although, at the time, I did not have much experience as a photojournalist but was convinced, I would get a scoop. At the opening, photographers and local officials surrounded Picasso. It was impossible to get a good shot, so I waited until all the press people had left. Just as Picasso was about to leave, the housekeeper arrived with his children Claude and Paloma. My chance had come, and I photographed Picasso holding Paloma in his arm, little Claude standing beside him. That one photo was at the origins of my friendship with Picasso. He liked the picture and agreed to photographs at his pottery studio in Vallauris.

To watch Picasso work was an incredible and decisive experience. I never before saw a work of art being created. He painted a bullfight scene on an unglazed clay plate. His eyes followed steadily the outlines that seemed to already exist, and it looked as if he relived an important stage at the corrida. When I heard Picasso tell Suzanne Ramié, the owner of the Madoura Pottery: "Lui, il ne me dérange pas" (He does not disturb me), I felt immensely relieved. It meant, I was permitted to visit Picasso again and indeed, I saw and photographed him regularly for over 20 years.

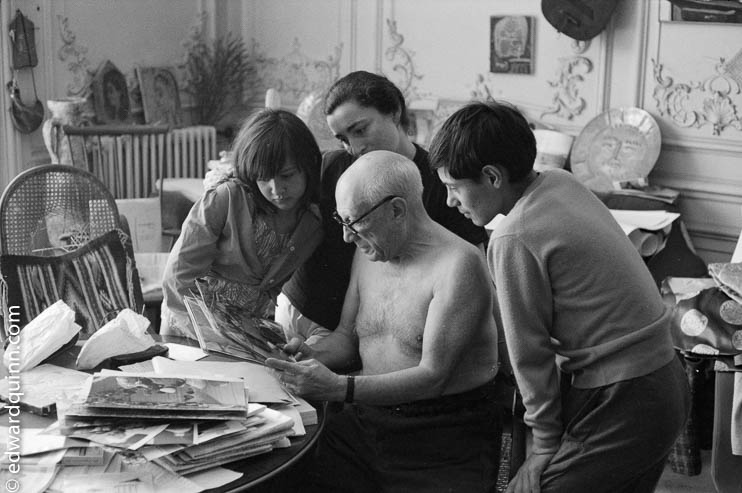

Whenever I went to see Picasso, I brought the photos of my previous visit and he and his wife Jacqueline studied and discussed them. When Picasso was in a playful mood, he would cheerfully help to make the picture livelier and donned a fancy costume or unique hat from his collection and pose.

Picasso did not at all appreciate when a photographer altered anything in his studio in an effort to make the photo look more attractive. The photographer Brassaï once moved slippers, he believed would disturb the composition. When Picasso came into the room, he straightaway noticed the change and said that this may make an amusing picture, but it would not be a document, because he would never place his slippers that way. "Or la manière dont un artiste dispose les objets autour de lui est aussi rélévatrice que ses oeuvres" (The way an artist has his things around him is as revealing as his work), he explained.

It was never easy to see Picasso, for him his work was predominating everything else. When he was going through one of these intensive working phases and they were quite frequent, he could absolutely not be disturbed. I only remember twice when Picasso actually asked me to come and photograph him. On one occasion, he had to undergo a surgical procedure in Paris. It was kept a secret, but he wanted me to take pictures of him before he left. The second occasion occurred when he was almost 90 years old. Very late one night, he worked on an etching and I could photograph and film him for hours. It certainly was his intention to be filmed so he could show how steady his hand still was.

Meeting Picasso was extremely important to me. Through him, I learned to observe and look at things in a different perspective. I became profoundly interested in modern art and had the opportunity to meet other artists.

In 1964, the New York Times assigned me to take pictures of Max Ernst, and I created a photo report at his home in Seillans, a little village in the Provence. Ten years later, having studied his work, I thought it would be very interesting to assemble a book, a collage of pictures of him and his Notes for a Biography. Since that last visit I had no contact with Max Ernst. He and his wife, the American painter Dorothea Tanning, still lived in the village, now in a bigger house they had designed themselves. Max Ernst received me but was annoyed as l had interrupted him at work. I explained my book project and he refused bluntly to cooperate. A few months later, I went up to Seillans again and tried once more to achieve his cooperation with a first mock–up. Max Ernst scrutinized it and finally said: "Mr. Quinn, I am very pleased with your work". After that, we had an exquisite lunch with the best wine from his cellar. From then on I visited and photographed him frequently. The book was published in 1976, the year Max Ernst died. He made a lithograph, one of his last works, especially for the book. I was deeply touched after learning he had signed the lithos as he was already very ill in the hospital.

Jean Cocteau was a celebrated artist and esteemed as a painter but also as a poet, dramatist, novelist and filmmaker. He always welcomed a journalist and put the visitor at ease. At all times, he had a story to tell, something new to show and the journalist left with plenty of information and good pictures, as Cocteau knew how to strike a pose. On most occasions, he made an effort to appear as bohemian and nonconformist as possible and often wore blue jeans, but they were well laundered, and the ends of the pants neatly folded up. He also frequently wore a leather biker jacket and, perhaps as a compromise to conformity, combined it with a collar and tie. Cocteau came to live in Saint–Jean–Cap–Ferrat at the invitation of Francine Weisweiller, a well–known socialite of the Paris café society. She owned the admirable Villa Santo Sospir. In return for Francine Weisweiller’s gracious hospitality, Cocteau transformed the white walls of the villa with paintings inspired by mythological stories and figures.

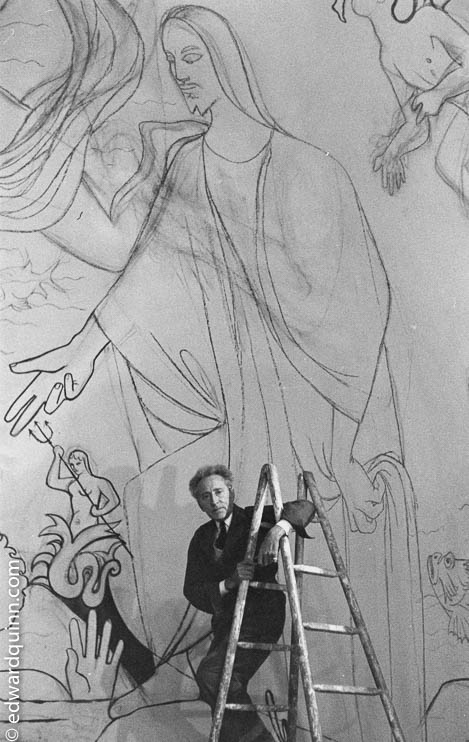

In 1956, Cocteau undertook the enormous work to restore and decorate the dilapidated and disused fishermen’s Chapelle Saint–Pierre in Villefranche–sur–Mer. He used motifs inspired by the Gospel representing three episodes in the life of Jesus. Local fishermen were the models for the murals.

Henri Matisse, who lived in Nice at the end of his life, built the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence. He devised the building plans and designed every detail of the chapel. The only photographs I ever took of Matisse were taken outside the chapel in 1953.

The same year, I photographed Marc Chagall and his wife Valentina Brodsky at their home in Saint–Paul–de–Vence. Chagall was a hard worker and did not like to be interrupted. He preferred to live inside his imaginary world of peasants, animals and flowers. His garden was full of flowers and at one occasion he said: "painting is trying continuously to rival with the beauty of flowers but never to succeed". Jean Dubuffet owned a home at the edge of Vence. He composed many landscape paintings there and used sand, tar, coal and other crude materials to create the surface texture.

The inauguration of the Fondation Maeght took place in Saint–Paul–de–Vence in 1964. It was the intention of Aimé Maeght, the art dealer and collector, and his wife, Marguerite, to create a place that would be a rendezvous for art lovers as well as people out for a stroll. Aimé and Marguerite Maeght had been greatly affected by the death of their youngest son and after that were advised by friends to develop a modern art center not only for their own collection, but also for newly acquired works. The notable architect Josep Lluis Sert was asked to design the building, and as Miró, Chagall, Giacometti, Tal Coat, Ubac, to name but a few, collaborated, the Foundation became a collective work of art. Joan Miró created numerous sculptures, among them L’Oiseau lunaire and, for the inside of a pool, the large Oeuf cosmique.

Alberto Giacometti visited the hall, where his sculptures are set up, at the inauguration of the Fondation Maeght. I happened to observe the artist while he looked intently at his work and the sculptures around him seemed to watch their creator. I met Alexander Calder while he was visiting Aimé Maeght in Saint–Paul–de–Vence. Calder is renowned for the innovation of mobile and stabile sculptures. He demonstrated a small mobile when I was photographing him and quoted Jean–Paul Sartre’s definition of a mobile: "Un Mobile: une petite fête locale, (…) une fleur qui se fâne dès qu’elle s’arrête" (A mobile, a small local celebration, a flower that fades as soon as it stops). Calder was very good humored and chortled every time a gust of wind swung the mobile

Hans Hartung and I were on friendly terms. I took pictures of him when he worked at his studio overlooking the sea on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. He always concentrated profoundly while he drew continual, sharp, slashing strokes with crayons and even brushes for his gouaches and oil paintings. He did not like to show his brushes, as these were part of the mystery of his technique to obtain the special effects.

I almost only photographed personalities or stars living or spending vacations on the Côte d’Azur but, from time to time, I took pictures of artists in other countries.

While I was visiting Salvador Dalí in Port Lligat on the Costa Brava in 1957, I hoped and expected to accomplish interesting and truly astonishing pictures. I knew Dalí was cooperative and extravagant enough to create situations a photographer would appreciate. I did not get disappointed. Dalí welcomed me and politely led me around his beautiful house. He introduced his Russian born wife, Gala, posed beside the big polar bear in the entrance hall and showed the water gun he uses to shoot octopus ink on sheets of paper to create a background. In his studio, he also let me look at a giant painting of a horse he had already worked on for three months.

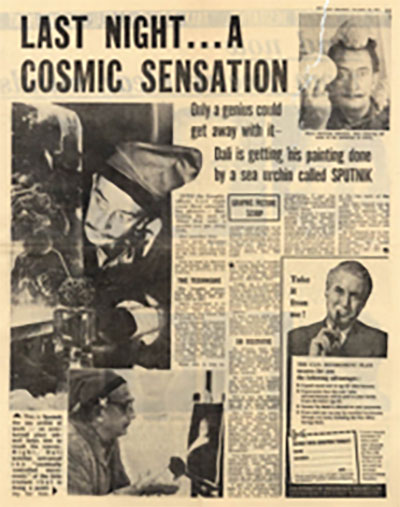

Most of all Dalí wanted to demonstrate his newest discovery. He dressed up for the event, putting on a fancy jacket and a dwarf hat. Later, he introduced the sea urchin he calls Sputnik and showed how it composes a painting. He inserted a very light feather of a swan into the sea urchin’s mouth. The mouth, with its five teeth, works like a hand and clenched the feather. Then, he placed the sea urchin in front of a sheet of paper, which was blackened with octopus' ink, and the sea urchin marked the paper with decorative lines in "cosmically controlled movements" as Dalí explained. The sea urchin repeated the movements also with a dried flower. Dalí insisted that some sea urchins are more talented than others. It was a very memorable day and I was highly satisfied with the photographs. The English newspaper Sunday Graphic published the reportage under the title: "Last Night…a Cosmic Sensation".

I remember very clearly one of my first meetings with Francis Bacon in London. He led me straight to the tiny kitchen of his one–bedroom apartment. His cleaning lady or "cleaner–upper", as Bacon used to say when he put on a cockney accent, joined us and made strong cups of English tea. We stood there, talking and sipping our teas. I cannot but wonder what she thought about the paintings, which filled the very messy studio on the ground floor. The kind woman must have been also amazed and overwhelmed by so much disarray and her sense of professional pride could even have revolted against the hopelessness of tidying up and cleaning thoroughly. In addition, I was having difficulties to imagine how she undertook the very frightening experience of climbing up the narrow, unsteady stairs that looked more like a ladder and led to the bedroom and kitchen on the top floor. I also wondered how Bacon negotiated those stairs after one of his legendary nights at a London restaurant where he would imbibe more alcohol than two large men are usually able to manage. But Bacon seemed to stay sober after at least a couple of bottles of champagne or a row of glasses of whiskey. I remember that I had to undergo somewhat of a test before Bacon accepted me. After our first real meeting, he invited me to his favorite Soho restaurant. I joined him eating a good dozen of oysters along with lots of drinks. Then, we went through a beautiful four–course meal and I drank at least four times more alcohol than I was accustomed to. Nevertheless, it seemed that I carried on a more or less intelligent conversation about art and especially about Picasso for whom Bacon had great admiration and respect. I do not remember how the evening ended, but whatever happened, I must have conducted myself nobly, because I passed the entrance examination to the Francis Bacon circle of friends, in other words, the Colony Room Club. After that, every time I met Bacon in London, we had a talking session at the comfortable surroundings of a Chelsea or Soho restaurant instead of a working session at his studio. Bacon was happy just to talk.

Much later, I was allowed to get to know the creative side of the artist and Bacon let me photograph at his studio. It was quite an experience as one can see from the pictures. Our photo sessions were normally confined to photographing him at the apartment or the Marlborough Gallery and sometimes at his studio in Paris.

Bacon did not like to discuss his art and I did not press the subject.

In 1983, I saw large sized linoleum cuts by Georg Baselitz at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Years before, I photographed Picasso working on some small linocuts and imagined that the artist who made such monumental ones must be exceptional. A few years later, I read a comprehensive article about Baselitz and became more and more interested in meeting him. I had the opportunity to do a monograph on his work and showed him the mock–up at Schloss Derneburg in Germany. Despite some language problems, Baselitz did not speak English and my knowledge of German was very limited, we got along very well and already on this first visit, we agreed to create a photo book together. From then on, I visited Baselitz quite regularly and was especially eager to photograph him in his element, at work, and show, as far as that was possible, the difficulties an artist has to face in his creative work. During these working sessions, Baselitz and I established a visual dialogue between painter and photographer. Neither he nor I liked or needed to talk as we worked. I communicated with him through my photography, I made images and so did Baselitz and in that way we had a conversation while creating our pictures.

Today with the dominance of television, the visual language is one of the most important means of communication. Photography is also a valuable communication medium. Photographs are, above all, stopped moments of action but unlike television, a photograph offers the possibility to analyze and reflect on the full sense and significance of an event. Artists are not always good or easy models; they very often are self–conscious and think their work should talk for them. However, a picture of an artist taken at his studio or his home, at the right moment, can certainly be revealing and I always tried to show the person behind the personality and the human behind the artist in my photos.