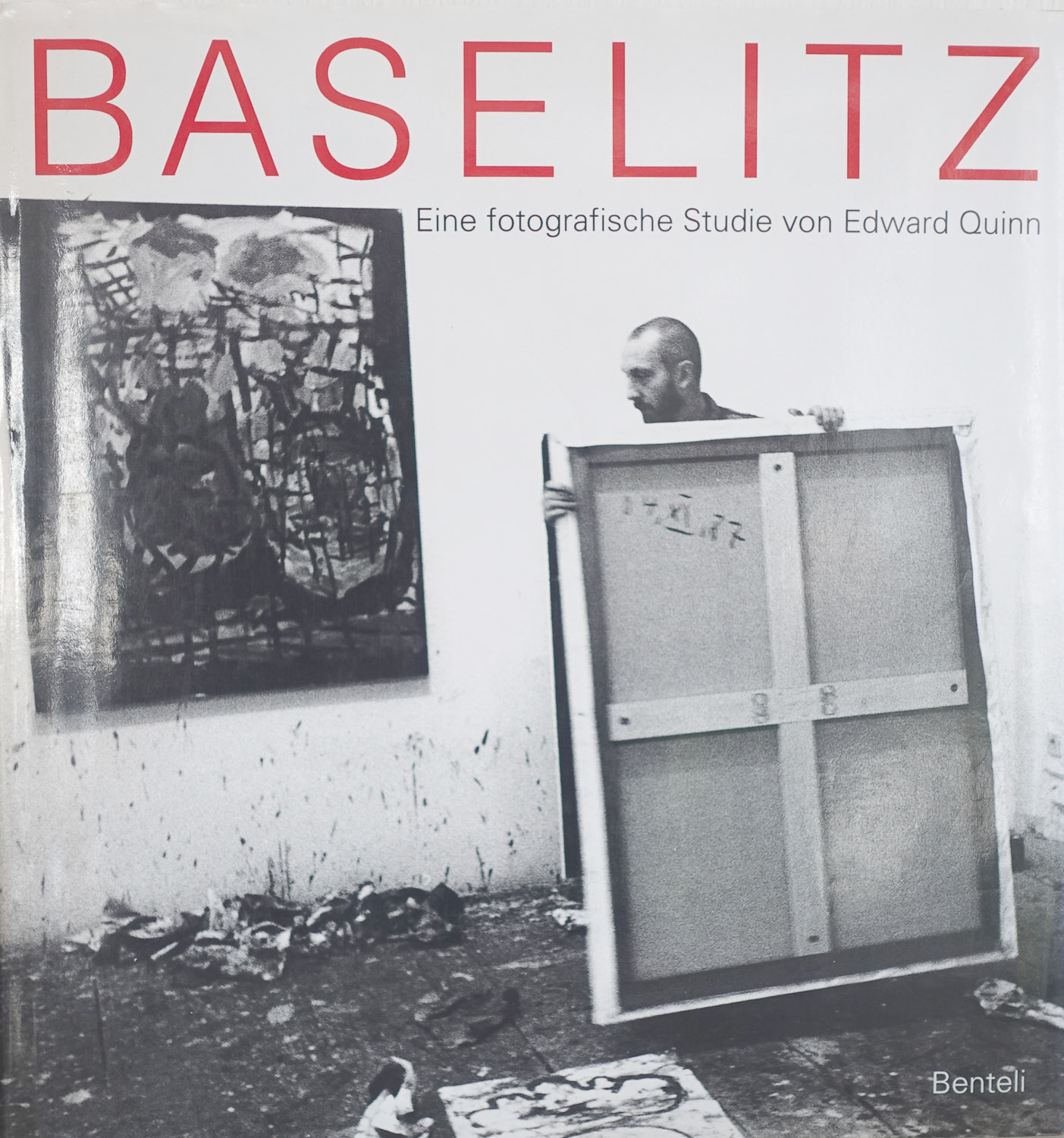

Georg Baselitz

by Edward Quinn

The story of making this book began when I visited the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1983 and saw an exhibition of Georg Baselitz' and Rolf Iseli's monumental wood-cut prints. I was very impressed by these works which looked like paper tapestries, and I imagined and appreciated the amount of work involved in doing such unusual giant sized prints.

My immediate reaction on seeing these prints was to relate this work to the linocut work which Picasso had done. I thought that Picasso, who I knew was always curious about and interested in other artists’ work, would have been fascinated by these large prints and that he would have been in sympathy with Baselitz as a fellow-craftsman, but also envious of Baselitz’ ability to do such large-sized wood cuts.

This first contact with the work of Baselitz was already an indication for me that he must be an artist out of the ordinary. From then on I kept his name in mind and followed the progress of his work.

A few years later I became involved in a project of doing a monography of Baselitz' work. I was able to get in touch with him and when I called he said he was familiar with my photographic work and agreed that I could come to see him.

My first meeting with Georg Baselitz took place at his home Schloss Derneburg in Germany on a cool spring day. Baselitz received me in his imposing library which also serves him as a living room. I had prepared a maquette for the monography project and I wanted to get his reaction to this. As I had never met Baselitz before, I was apprehensive at first, but I was quickly reassured, getting the impression at once that Baselitz was a very sincere down-to-earth man.

After our preliminary conversation over a cup of tea, I showed him the maquette of the monography. He had been joined by his wife Elke and his secretary Detlev Gretenkort. While they looked carefully at the maquette, I got out my unobtrusive Leica camera and, as I usually do when visiting an artist, I took some photographs. To my relief, Baselitz' reaction to the maquette was very favorable and he agreed to give me his collaboration.

It was very important for me during that first meeting that we had a very good "rapport", despite some language difficulties. I realized that Baselitz was someone I would enjoy working with. I was also impressed and stimulated by the atmosphere of Schloss Derneburg and I suggested that it might be a good idea not only to do a monography, but also a photographic book which would show the artist in his element. Baselitz liked the idea and we began to work at once, Baselitz guiding me around his ateliers. I took some photographs, some of them are included in the book, and these photographs were the starting point of the project.

From then on I had the possibility of visiting and photographing Baselitz regularly. During these working sessions, Baselitz and I were able to establish a kind of visual dialogue between a painter and a photographer. Neither Baselitz nor I liked or needed to talk as we worked. I could communicate with him through my photography as well as with words. I made images and so did Baselitz and in this way we had a kind of dialectic while making our pictures.

Nowadays with the predominance of television, the visual language is one of the most important means of communication. But photography is also an important communication medium. Photographs are above all stopped moments of action, but unlike television, a photograph offers us the possibility to ponder over and reflect about the full sense and signification of an event.

My intent of doing this book is to try and show how a photographer by his constant and perceptive observation, working with an artist over a long period of time and following with an ever-ready camera eye the progress of the artist's work, can be a valuable witness and can contribute through his photographs to our understanding and insight of the difficult and somewhat mystical pursuit of creating a work of art.

An example of the importance of a photographer's observation and work can be seen in the chapter THE GENESIS OF A PAINTING (DAS MALERBILD). The camera has recorded the torment of the painter and shows that he cannot always represent to his entire satisfaction what seemed to be his initial visualization of the painting. But we can also see in the same sequence how he goes on and strives to bring the work to a finality, sometimes being confronted with surprises even for himself. By following the progress of the work. as recorded by the camera, one can see the changes not only in the composition itself, but also in the approach of Baselitz and how finally he finds a solution through his instinct and sensitivity.

Baselitz shows that another factor which often intervenes in the difficult process of creation is the technique of painting itself, the necessity of getting the right color, tone and density. These are additional hazards for the artist to surmount before he can achieve his aim, to make a work of art.

When Baselitz reaches the point when he feels satisfied, it means that for him the work is a valid work of art which embodies his ideas, thoughts, reflections, intuitions and craftmanship.

Even though we can follow visually the process of creating an art work, the mystery behind this creation still remains. The artist has not always total control over his sainting. Picasso once said: "The painting makes me do what it wants to".

As Baselitz does not like to have anyone around, especially a photographer, while he works, it should be emphasized that it was a rare privilege to be allowed into his studio while he painted, without being handicapped by restrictions. It is an additional challenge for an artist to have to share the precious isolation and silence of this studio, especially with the probing camera eye capturing the moments of reflection.

It was not always easy to keep up the sustained effort needed to document Baselitz at work. He is a powerhouse of energy and — for hours on end without a break which requires great stamina. He has no pupils or assistants and must do most of the moving around and positioning of the heavy paint-loaded canvases himself.

As Baselitz does all his work with great enthusiasm, this is contagious and to be efficient, it was necessary for me to work with the same enthusiasm and constant attention through many hours and days. From a photographer's point of view it should be said that not every photographer has the patience or interest to spend days trying to record and document the life of an artist and his work. But for me this was my aim: to try to catch the famous “decisive moment”, or the sequence of decisive moments. This is for me the real art of photography: to be involved in interesting situations where one brings all one's experience and know-how together for a fraction of a second, so as to capture on film some great or important moments of life.

Although the emphasis in this book is on the visual, the text has also an essential place, an unusual and important feature in each chapter is the text by Georg Baselitz. It is a kind of commentary with his explanations, impressions and reactions to his own work, inspired by the photographs.

This is an invaluable contribution to the book and considerably heightens the documentary interest of the photographs. This reflective and lucid viewpoint of the artist about his work and himself, judging his work in a very objective way, sometimes pointing out a satisfying achievement or explaining an error, will certainly help the readers to get a more complete impression of Baselitz' total involvement in his work and of his determination to go to the limits in his art.

I hope this book will help to give a better understanding of Georg Baselitz' efforts to try and expand to the utmost his possibilities of creating significant and durable works of art. The art historian Andreas Franzke says "For Baselitz, each work is a weapon with which to uphold the creative power of the individual. He offers his contemporaries, intimidated by technological progress and unceasingly defenseless in the face of civilization and all its constraints, the clear evidence of his own unconditional individualism."